Neighbors, friends and family gathered at the Pinchbeck home on November 13, 1829. They were there for the estate sale following Mary Pinchbeck’s death in July 1829.[1] This was a common practice of the period. Estates were inventoried, appraised and sold, with the proceeds divided as directed by the will or chancery court.

Was it hard for the Pinchbeck children to watch the furnishings of their childhood home sold? Mary’s son, Thomas, purchased her spinning wheels and H. Rudd (possibly a nephew) purchased her flax wheel. Thomas purchased the most expensive item of the sale, a yoke of oxen for $41.75. The sale brought in $265.00. View the complete sale list here.

The contents of the sale reveal much about John and Mary’s life. They were farmers, had horses and livestock and even a gig. A set of carpenter’s tools suggests John practiced some carpentry. The furniture included a desk, tables and chairs. They didn’t have luxurious items like silver, china or goblets, but the furnishings indicate a comfortable lifestyle.

The estate appraisal identifies nine slaves. They were valued and assigned to the Pinchbeck children.[2] Since none were sold at the sale, it appears the children were satisfied with the division. The nine Pinchbeck slaves were valued at $2,104.00. [3]

- Jacob, a negro man, $383, assigned to William

- John, ditto, $350, assigned to Robert

- Hill, a likely lad, $300, assigned to George

- Luesy, a likely girl, $283, assigned to Nancy

- Winney, ditto $283, assigned to Thomas

- Lucy, an old woman, $100, assigned to Thomas

- Ellick, a boy, $225, assigned to Mary

- Gustus, ditto, $180, assigned to Mary

- Dick an old man not worth anything by consent of parties & from a wish of his former owners for him to remain in the family was by mutual consent put up to the lowest bidder and was taken by William Pinchbeck at fifteen dollars who is to keep and support him for life.

These nine enslaved individuals were the bulk of the wealth of the Pinchbeck family. As slaves they were a commodity, just like the cattle and horses. The only mention of their names is found in the estate papers and their division among family members is a reminder of the cruel and heartless nature of slavery.

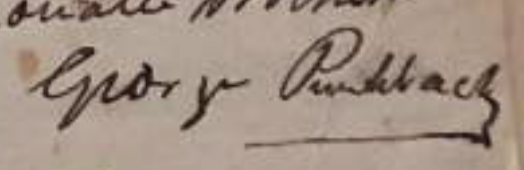

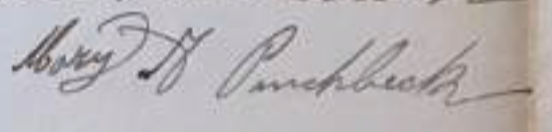

John Pinchbeck placed a high value on education.[4] He made provisions in his will for the education of his younger children. The estate paid Thomas for the tuition of his younger brother Robert.[5] The letter (part of the 1830 chancery cause) from George Pinchbeck demonstrates a good handwriting and ability to communicate. All of the Pinchbeck heirs (except George) signed their own names to a receipt for the estate proceeds. The Pinchbeck sisters, Mary Ann and Nancy signed their own names, indicating they, too, were educated.[6] It is curious that the estate appraisal contained no books. Perhaps Mary Pinchbeck distributed any books before her death.

Footnotes

[1] Chesterfield County, Virginia, Will Book 11, p. 654.

[2] Chesterfield County, Virginia, Chancery Cause 1830-035, Pinchback vs Pinchbeck, Library of Virginia

[3] The records in chancery causes provide vital clues for slave descendants researching their ancestors.

[4] John Pinchbeck’s Will, Chesterfield County, Virginia, Will Book 10, p. 273 – 274.

[5] John Pinchbeck Accounts, Chesterfield County, Virginia, Will Book 12, p. 182 – 183

[6] Chesterfield County, Virginia, Chancery Cause 1830-035, Pinchback vs Pinchbeck, Library of Virginia

My fourth great-grandfather James Ball’s patriotic service to the American Revolution was verified by the

My fourth great-grandfather James Ball’s patriotic service to the American Revolution was verified by the